Gabriel is a PhD researcher at the Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP). He is a plant ecologist with special focus on floristic patterns and distributions. Here, Gabriel shares his recent work on the diversity patterns in continental islands along the Brazilian coast.

Early career researcher Gabriel Pavan Sabino in front of a granite cliff covered with Tillandsia alcatrazensis (Bromeliaceae), an endemic species recently described by the research team [Photo by Gabriel Marcusso].

Personal links. Researchgate | Instagram

Institute. Universidade Estadual de Campinas – UNICAMP

Instituto de Biologia

Departamento de Biologia Vegetal, Campinas, São Paulo, Brasil

Academic life stage. PhD researcher

Major research themes. I’m interested in plant ecology and evolution, particularly in floristic patterns, biogeography, and species distributions. My current research focuses on the diversity patterns in continental islands along the Brazilian coast.

Recent paper (citation). Sabino, G. P., Pinheiro, F., Cabral, J. S., Koch, I., Marcusso, G. M., Tavares, M. M., Cunha, I. M., & Kamimura, V. A. (2025). Islanded Islands: Dual isolation drive distinctive and threatened floras of Neotropical maritime inselbergs. Journal of Vegetation Science, 36(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.70037

Current study system. Plant communities of Neotropical maritime inselbergs:

Inselbergs, which are isolated rock outcrops, host unique plant communities and are considered insular environments due to their distinct conditions, compared to the surrounding landscape. During interglacial periods, sea level rise can turn some of these inselbergs into true islands, further increasing their isolation from the mainland. This isolation promotes local adaptations and endemism, making these systems natural laboratories for studying ecological processes and the mechanisms that shape plant communities.

Motivation behind this paper. This study started with a pretty simple idea: to survey the plants growing on Alcatrazes Island, a stunning and ecologically unique island off Brazil’s southeastern coast. But the deeper we got into its flora, the more we started asking ourselves a bigger question: How does all this plant diversity compare to what we find on other islands? This question opened the door to a broader, macroecological view. However, we soon realized that it wasn’t enough to compare Alcatrazes to just any island. So, we turned our attention to islands with similar geological characteristics, shifting our focus to other coastal inselbergs, as well as to their continental counterparts. By bringing together plant data from these sites, we were able to dive deeper into how factors like oceanic isolation and climate influence both species richness and their evolutionary uniqueness. In other words, we weren’t just asking how many species live there, but also how different they are from one another in evolutionary terms.

An overview of Alcatrazes Island, located 35 km off the southeastern coast of Brazil [Photo by Luciano Candisani].

Key methodologies. We introduced the concept of maritime inselbergs (MIs), isolated rocky outcrops that became true islands after sea level rose, and, for the first time, explored the unique plant communities living on them. To understand how these ocean-bound systems work, we compared them with continental inselbergs (CIs). Instead of focusing only on species, we looked at the deeper evolutionary patterns behind them, asking how different these communities are—not just in terms of who’s there, but in terms of what lineages they belong to. Are the plants on MIs close relatives of those on CIs, or do they represent distinct branches on the tree of life? We also wanted to know if climate plays a role in shaping these patterns and whether certain conditions favor specific species or evolutionary histories. Beyond that, we examined the conservation status of the plants we found, using Brazil’s official Red List. Then we went one step further: We used modelling to simulate what might happen to entire evolutionary lineages under different extinction scenarios.

Landscape showing the rupicolous vegetation of Alcatrazes Island and, on the horizon, the mainland [Photo by Gabriel Pavan Sabino].

Unexpected challenges. A well-established idea in biogeography is that similar environments located closer together tend to share more species than those farther apart. However, in our floristic similarity analysis, we found the opposite. The MIs in Rio de Janeiro (The archipelago of Cagarras), which are only about 10 km from the nearest CI (like Pão de Açúcar), are actually more similar to other MIs located at least 280 km to the southwest. This highlights how strong the environmental filters imposed by the ocean can be in shaping the plant communities of these environments.

Fieldwork in such extreme environments is already a major challenge in itself. We experienced this firsthand while conducting fieldwork on Alcatrazes Island. This helps explain why floristic surveys on islands in Brazil are so rare. We also noticed this during our literature review, as we searched for floristic surveys to include in the compilation used for our study.

Returning to camp after a day of fieldwork. Moving across such steep terrain with all the equipment is a real challenge [Photo by Yan Marcos].

Major results. In addition to identifying that MIs possess a distinct floristic identity, we found substantial heterogeneity among the communities, with only 11% of species shared between them. Roughly 10% of all recorded species are officially threatened, underscoring the role of inselbergs as key refuges for endangered flora. Climate also played a major role in shaping these communities, especially variables like annual temperature range, temperature of the warmest quarter, and isothermality, which reflects how stable day-to-night temperatures are compared to annual shifts. Perhaps most striking, our models suggest that losing 25% of species could significantly disrupt the evolutionary structure of these communities. We argue that the most important insight from this work is understanding how plant communities assemble under a combination of permanent ecological isolation, due to the natural insularity of inselbergs, and temporary geographic isolation caused by sea level changes over glacial and interglacial cycles.

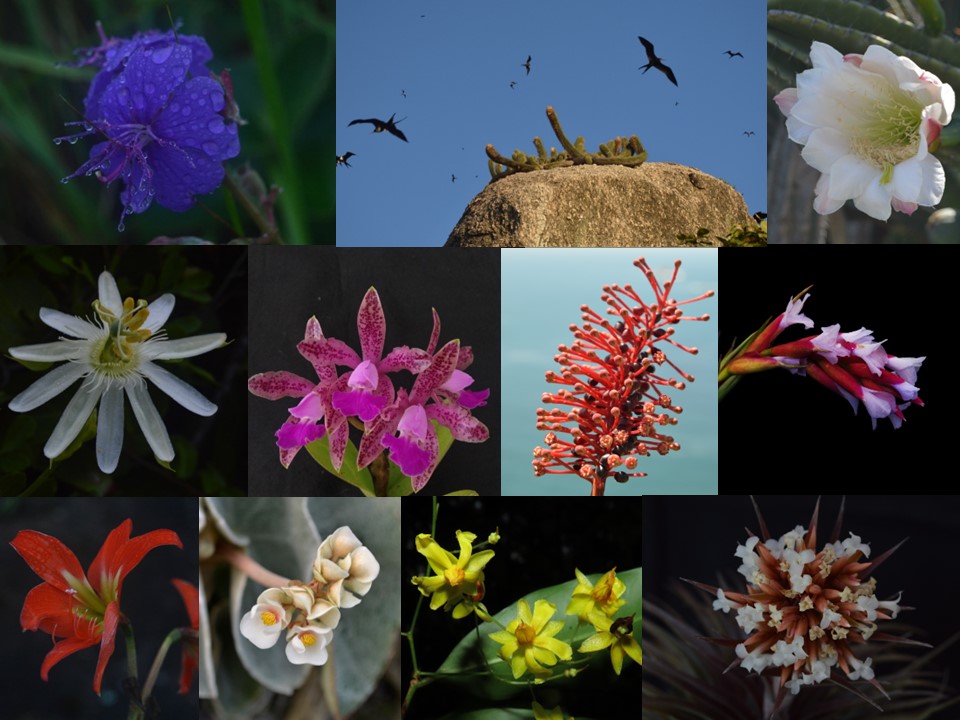

Some examples of the flora of Alcatrazes Island (left-to-right and top-to-bottom): Pleroma clavatum (Melastomataceae); Coleocephalocereus fluminensis (Cactaceae) and Magnificent frigatebird, Fregata magnificens in the background; Cereus hildmannianus (Cactaceae); Passiflora mucronata (Passifloraceae); Cattleya x intricata (Orchidaceae); Schwartzia brasiliensis (Marcgraviaceae); Tillandsia uiraretama (Bromeliaceae); Hippeastrum blossfeldiae (Amaryllidaceae); Begonia venosa (Begoniaceae); Ouratea parviflora (Ochnaceae); Tillandsia alcatrazensis (Bromeliaceae) [Photos By Gabriel Pavan Sabino].

Next steps for this research. We know this is a multi-generational effort, but we are highly motivated to expand our sampling across different types of islands along the Brazilian coast. Currently, we are focusing on how functional traits vary between insular species and their continental populations. We aim to identify the adaptive strategies of plants that are isolated from pollinators, herbivores, and other plant species that would normally compete with them in continental environments but are no longer present in insular systems. This will provide important ecological insights and help us understand how evolutionary processes operate in plant communities within highly diverse systems.

If you could study any organism on Earth, what would it be? One of the organisms that intrigues me the most are rupicolous plants. They germinate and anchor their roots directly onto rocks in extremely harsh environments, often exposed to strong winds, high salinity, and extreme temperature fluctuations. They are true champions of adaptation! I began studying them accidentally during my PhD.