Axel Arango is a postdoctoral researcher at the Universität Würzburg, Germany. He is a evolutionary biologist with special focus on Macroecology and Macroevolution. Here, Axel shares his recent work on how ecological specialization, rather than geographic dispersal, shapes diversification in Emberizoidea songbirds.

Axel Arango, postdoc at the Universität Würzburg, Germany.

Personal links. https://axelarango.github.io

Institute. Center for Computational and Theoretical Biology (CCTB), Universität Würzburg, Germany

Academic life stage. Postdoc

Major research themes. Evolutionary Macroecology; Biogeography; Phylogenetics; Macroevolution

Current study system. Birds

Recent paper (citation). Arango, A., Pinto-Ledezma, J., Rojas-Soto, O., & Villalobos, F. (2025). Broad geographic dispersal is not a diversification driver for Emberizoidea. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 292(2039), 20241965.

Essay. Emberizoidea is a bird lineage that has long captivated both scientists and cultures with their vibrant plumage, beautiful songs, and ubiquitous ecological range, inhabiting the whole of the New World and most of Eurasia, and Africa. Their diversity includes tanagers, cardinals, sparrows, warblers, and buntings. Darwin observed the beaks and diet of Galapagos finches, which played an essential role in the inception of the natural selection theory while later becoming a classic example of adaptive radiation. A century later, MacArthur observed that some good warblers were sharing the same trees but using them subtly differently. These species of the then Dendroica, now Setophaga genus became textbook examples of niche partitioning. But long before evolutionary and ecological theory, pre-Hispanic cultures across the Americas had already incorporated Emberizoidea into their worldviews. The Mexicas honored the tzanatl (Great-tailed grackle) and oropéndolas (Montezuma’s oropendula) for their song and majesty; the Mayans saw cardinals as symbols of fertility and life.

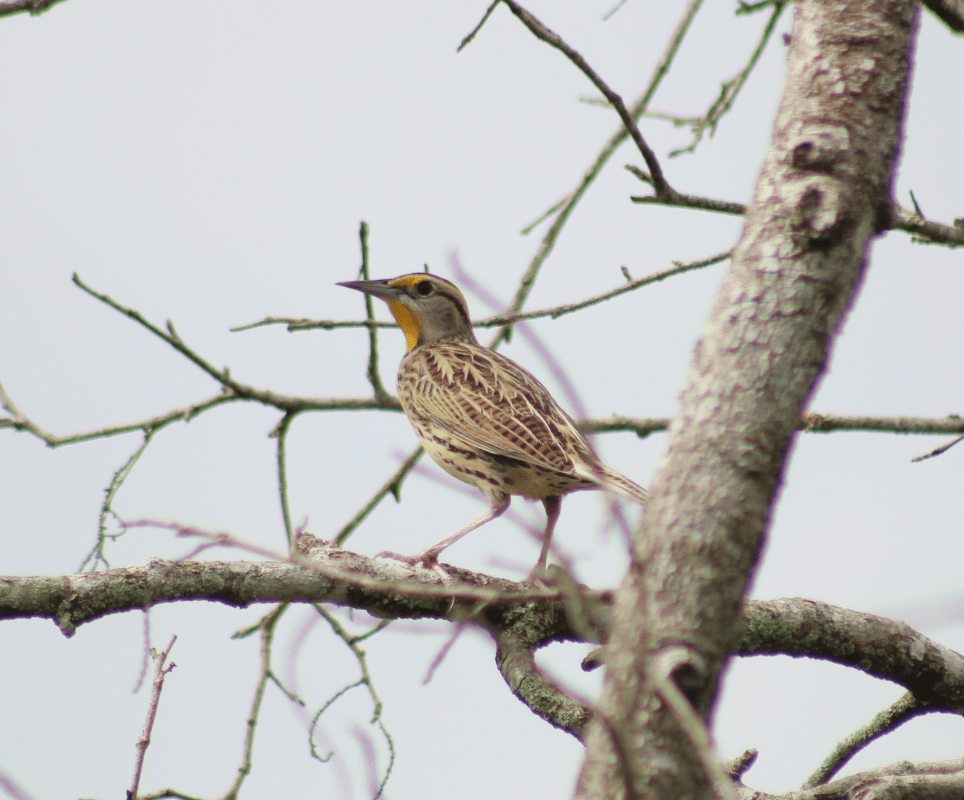

Pradero Tortillaconchile (literally translated to “Meadow Tortilla with chilli”; Sturnella magna) in the dry forest of Ozuluama,Veracruz. Distinctive member of the Icteridae family.

While finishing my Master’s, I became captivated by this dazzling avian diversity. As someone from the Americas, I couldn’t help but notice how unevenly bird species are distributed across the continent. Some areas (like the Andes or Mesoamerica) are bursting with species, while others have fewer species. Why? What drives these differences?

A leading hypothesis in evolutionary biology is that geographic dispersal (species colonization of new areas) plays a central role in triggering speciation. This idea presents an intuitive possibility: when a lineage moves into a novel area, it might escape competitors and predators, find unexploited resources, and become geographically isolated. That isolation can break gene flow, allowing populations to diverge, adapt to new conditions, and eventually become a distinct species. So, in theory, the more a group disperses, the more opportunities it has to diversify.

So, is this actually true for Emberizoidea?

To find out, we used phylogenetic bioregionalization to define geographic regions based on where species live and their evolutionary relationships. Then, we reconstructed the historical biogeography of lineages using several models of range evolution. This approach allowed us to figure out the most likely scenarios of when and where lineages expanded into new territories (dispersal) and when their distribution shrunk (range contraction). Finally, we quantified the changes in evolutionary rates across the Emberizoidea tree, detecting when certain lineages had higher speciation rates, and asked whether lineages that moved into new bioregions actually diversified faster.

The iridescent tzanatl (Great-tailed grackle; Quiscalus mexicanus), former Aztec treasure. Now in most Mexican cities (and beyond).

The surprising answer? Despite the proposed hypothesis, the lineages that dispersed didn’t speciate faster.

In fact, most diversification in Emberizoidea seems to have happened within regions, not after colonizing new ones. We even tested this statistically by comparing nodes that dispersed with similarly aged nodes that didn’t and found no consistent increase in speciation. Furthermore, families that maintained stable ranges over millions of years tended to be more diverse. In short, staying put may be more beneficial for speciation than spreading out.

This challenged a major assumption. Dispersal is often treated as the spark that lights the diversification fire. For instance, the Corvidae family, shows significantly elevated rates of both speciation and regional transition, suggesting that diversification is promoted by frequent dispersal and colonization events (Kennedy et al., 2017). In anurans, the interplay between regional geomorphology and species-specific dispersal abilities drives distinct diversification patterns (Fouquet et al., 2021), and likewise, in plants, the Chamaesyce clade of Euphorbia diversified through repeated dispersal followed by local adaptation (Yang & Berry, 2011), but in Emberizoidea, dispersal looks more like a side story.

Chingolo (Rufous-collared sparrow; Zonotrichia capensis) in the temperate forest. An abundant South American bird of the Passerellidae family.

Currently, we’re focusing our attention to ecological specialization. If movement isn’t the main driver, maybe what matters more is how lineages adapt to specific roles within their environments. Could specializing in certain diets or habitats drive diversification from within a stable range? For example, Galapagos finches could also dramatically illustrate how a single ancestral population on a stable island system gave rise to diverse species through dietary specialization. Or how wood warblers could have specialized to have different foraging behaviors, minimizing competition and fostering divergence. To test that, we’re exploring the effects of traits like diet, habitat specialization, and foraging behavior in speciation dynamics.

Ultimately, this work has reshaped how we think about evolution in a group of birds and perhaps even reminded us that sometimes, the story we do not expect is the one worth telling.

A colony of Montezuma Oropendolas (Psarocolius montezuma) in the Neotropical Forest.

Reference list.

Kennedy, J. D., Borregaard, M. K., Jønsson, K. A., Holt, B., Fjeldså, J., & Rahbek, C. (2017). Does the colonization of new biogeographic regions influence the diversification and accumulation of clade richness among the Corvides (Aves: Passeriformes)?. Evolution, 71(1), 38-50.

Fouquet, A., Marinho, P., Rejaud, A., Carvalho, T. R., Caminer, M. A., Jansen, M., … & Ron, S. (2021). Systematics and biogeography of the Boana albopunctata species group (Anura, Hylidae), with the description of two new species from Amazonia. Systematics and Biodiversity, 19(4), 375-399.

Yang, Y., & Berry, P. E. (2011). Phylogenetics of the Chamaesyce clade (Euphorbia, Euphorbiaceae): Reticulate evolution and long‐distance dispersal in a prominent C4 lineage. American Journal of Botany, 98(9), 1486-1503.