Deputy editors-in-chief at the Journal of Biogeography (JBI) set up an 11th hour meeting with Wiley trying to resolve the two-month ongoing dispute about affordability, equity, and editorial independence. Initial reports are that the talks failed. The pending mass resignation of the remaining associate editors takes effect.

This blog and related twitter accounts have been relatively quite over the past few weeks, not because nothing has been happening (see below!), but, because the editorial board wanted to give an 11th hour meeting with Wiley chance to make progress. The meeting had been negotiated by the remaining deputy editors-in-chief, who have been busy impressing upon Wiley the gravitas of the matter, the potential damage to the journal’s and publishers’ reputations being caused by Wiley’s as yet inadequate responses, and Wiley’s continuing need to address the editorial board’s concerns about affordability, equity, and editorial independence at the journal.

The sad news is that initial reports indicate the editorial board’s last ditch efforts to make progress have failed. This means that the resignations of the remaining ~1/3rd of the Associate Editors — offered three weeks ago contingent on progress in discussions with Wiley (but accepted immediately by Wiley!) — will now go into effect on 28th August.

It seems Wiley does not know how, and/or is unwilling, to listen and collaborate with their editorial boards. There have been many opportunities: contract discussions in late 2022; the resignation of the first deputy editor-in-chief in January 2023; two all-hands meetings with the editorial board in early March; a month of discussions in April culminating in resignation of the editor-in-chief in May, the start of the associate editors’ work stoppage in June (with a target data of 31 June for resolution), and continuation of the work stoppage and beginning of resignations in August. All of these events signalled to Wiley that these were serious matters and needed attention. Not once did they engage meaningfully.

It’s possible Wiley’s strategy is to encourage resignation of editorial boards that are asking for improvements, so Wiley can replace them with more compliant boards, thus ratcheting forward their unaffordable, inequitable, publication models and decreasing editorial independence at the same time. Indeed, this seems to be happening at J. Biogeography: having created a vacuum by firing the current editor-in-chief — an independent academic and practicing biogeographer — the word on the street is that the next editor-in-chief will be a Wiley employee, lacking serious credentials in biogeography, transferring in from Wiley’s Ecology & Evolution journal, which is something of an APC/OA clearing-house whose “overriding philosophy is to be ‘author friendly’ and editing practice is to ‘look for reasons to publish.’” This appears to confirm beyond any doubt that Wiley’s primary concern is fiscal, not scientific. It is a desperate fall from grace for a journal of JBI‘s prior standing.

It’s reasonable, therefore, to ask whether the actions of the editorial board at JBI have been successful. If the ultimate outcome was a mass resignation, why not just do that in the first place? What was gained by over 8 months of protracted, failed, negotiations?

We believe we have demonstrated a new and effective way to take action:

– This was the first ever #WorkStoppage by #AssociateEditors at a Wiley journal. (Possibly the first for any large publisher?).

– It is clear from our interactoins with Wiley, that they are shaken; this is causing them substantial concerns.

– The extended timeline allowed us to share with the community the extent of our efforts to build a more positive outcome for the publishing community; and to demonstrate that time and time again, Wiley refused to engage seriously.

– This created an unprecedented cross-journal movement that is spreading: associate editors at other journals are asking their chief editors to engage with these issues; someAEs have resigned or started work stoppages at other Wiley journals. Editors-in-chief at related journals are likewise asking Wiley to engage with these issues, lest they face additional reputational loss.

– It became an international conversation, a hopeful harbinger of change, e.g. at Retraction Watch (story 1, story 2, story 3), Times Higher Ed, Andy Stapleton, Metin Aytekin, and Khrono (a newspaper for universities in Norway)

– Over half of authors who submitted their manuscripts during the work stoppage, and who were informed about these issues (after Wiley declined to do this!), have asked that their manuscripts be unsubmitted so they can publish elsewhere (see some options below).

– Authors of some manuscripts at more advanced stages are taking their reviews and decisions from JBI (the journal’s default policy introduced by this board) and pursuing ‘fast track’ submissions at society journals such as Frontiers of Biogeography (published by the International Biogeography Society using the eScholarship platform [*not* part of the ‘Frontiers in‘ series).

– We have heard from multiple publishing platforms about offers to set up new biogeography journals with better practices, which we are following up.

– Societies around the world have also started to sign on to a Joint Statement on Scientific Publishing, endorsing societies’ leading roles in more affordable, equitable, independent publishing that further supports the communities they serve.

The editorial board at JBI has arguably broken new ground in how to demonstrate effectively against modern exploitative publishing practices. We have done all we can for JBI. Many of us are now committing our editorial and reviewing services to only society-owned journals; others are taking a well-earned break. As we move into these next ventures, we thank the broader community of authors, editors, and reviewers for their patience and overwhelming support; we know this has had impacts on you too, for which we apologize; Wiley could’ve avoided those at any point in the past 8 months. We anticipate Wiley hopes the ”noise’ from the community will simply dissipate as the board leaves. We encourage everyone to continue to make your opinions and values clear to Wiley privately and publicly and by investing your authoring, editing, and reviewing expertise in other journals, preferably society journals. Together, we can make scientific publishing #BetterPublishing.

To help build on the advances made by JBI’s outgoing editorial board, we provide the following three resources:

A. The list of the negotiating points prioritized by the JBI Associate Editors (see ‘A‘ below). This does not mean lower-ranked issues are less important — they all need to be addressed — rather it provides a roadmap for where Wiley (and other publishers) need to make change first to simply show they are sincere in wanting #BetterPublishing for all. We recommend existing and incoming editorial boards at for-profit publisher-owened journals to ask for as many of these points as possible; failing that, consider a work stoppage, and recommend alternate society-owned journals in your field.

B. A partial list of alternate, society, journals that publish biogeographical research (see ‘B‘ below).

C. A developing list of additional negotiating points for potential future associate and chief editors, based on our and others’ experiences.

A. Negotiating points prioritized by JBI Associate Editors.

1. Irrespective of the publication model, OA fees for JBI must be more

affordable, reflecting the actual cost of publication, which will help

reduce inequity globally.

2. Irrespective of the publication model, there must be a meaningful

waiver program so that researchers with insufficient funds are not

disadvantaged.

3. Goals around growth must not come at the expense of the quality of

the journal. The former should be driven by improvements in the latter.

Therefore, goals to grow the journal must be accompanied with matching

additional investment. At this point in time, the senior editorial team

is against increasing the number of accepted papers. Rather, Wiley must

invest in strategies that will increase the standing of JBI in

comparison to other journals of comparable scope.

4. As one of a variety of possible futures, a model must be developed

for the possible case of fully flipping JBI to Gold OA — irrespective of

whether there is or is not currently an explicit plan. In this, Wiley

must guarantee a full or partial waiver (as needed) to any author whose

manuscript is accepted but who does not have the funds to pay the

regular APC.

5. Rewards for AEs must be reinstated to prior levels, i.e. at least one

OA article per year in JBI (as first or senior author) or equivalent

value (depending on the editors’ circumstances).

6. More investment must be made in the scientific (Biogeography)

community. We suggest levels akin to those returned to societies as a

benchmark, as they are analogs for the biogeographic community that

supports Wiley’s business model for JBI. Also see above re. APC waivers,

Judith Masters Memorial Fund, honoraria, recompense for AEs. In

addition, this means increases in support for global colloquia. And it

necessitates annual inflation-adjustment for all such investments;

anything less is an effective disinvestment.

7. Independence of the Editorial Board must be reified, and also

clarified through contracts (e.g. exclusion of growth targets, transfer

targets, NDAs, etc).

8. Reinvestment in Production, revision of workflows, and returning

oversight to the Editor-in-Chief.

9. In addition to the above, other elements supporting the journal’s

stated ‘Global Biogeography Initiative’ should be enacted:

· free language support for non-English-as-a-first-language

author teams during editorial and peer review

· the Judith Masters Memorial Fund, while appreciated, is

insufficient to cover all costs of attendance at an international

meeting. The fund should be increased so that it would cover all

expenses of attendance at an international conference/lab, for multiple

eligible researchers.

10. Revise the ScholarOne interface and transfer scheme to facilitate

JBI’s editorial policy on decisions, including transfers, encouraging

sharing of decisions and reviews with any journal.

Two of the original twelve points were prioritized for negotiations by future potential incoming associate and chief editors:

i. Non-Disclosure clauses must be removed from editor contracts.

ii. dEiC honoraria should be returned to pre-2019 levels. All honoraria

should be automatically annually adjusted for Inflation. If more work is

shifted to people receiving honoraria, the honoraria should increase

accordingly; criteria for calculating honoraria should be transparent.

See additional negotiating points for potential future associate and chief editors.

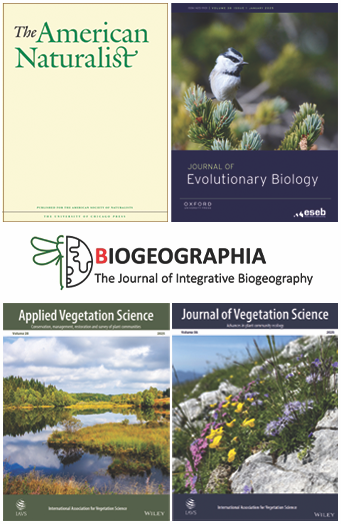

B. A partial list of alternate, society, journals that publish biogeographical research

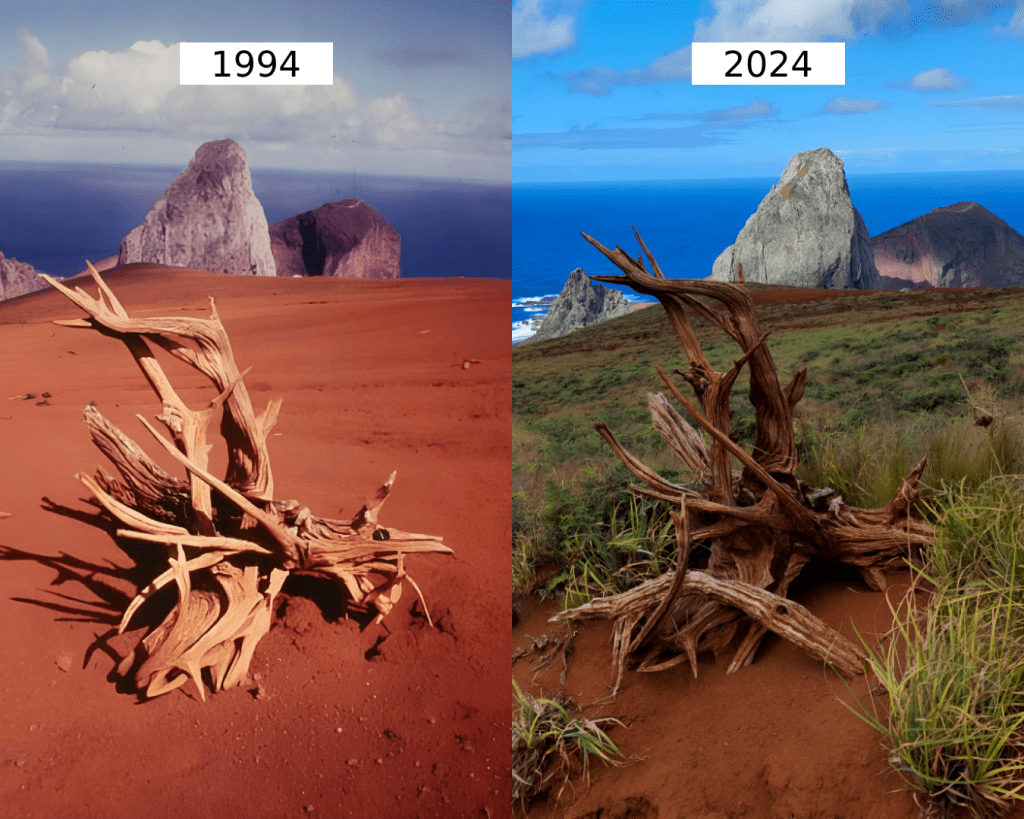

If considering another venue for your biogeographical work, a few years ago we did an analysis of journals publishing biogeography https://escholarship.org/uc/item/67n7x3zk (see Fig 1), which may provide some ideas. We recommend Society-owned journals as these give more back to the community. Some are published by Wiley; some are not.

Society-owned journals that publish biogeographical works include (but are not limited to):

American Journal of Botany (published by Wiley)

American Naturalist (published by U. Chicago Press)

Biological Journal of the Linnean Society (published by Oxford Academic)

Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society (published by Oxford Academic)

Ecography (published by Wiley)

Sister journals https://nordicsocietyoikos.org/publications (published by Wiley)

Evolutionary Journal of the Linnean Society (published by Oxford Academic)

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (published by Oxford Academic)

Evolution (published by Oxford Academic)

Journal of Mammalogy (published by Oxford Academic)

Journal of Vegetation Science (published by Wiley)

Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation (published by Elsevier)

Proceedings of the Royal Society, B (published by Oxford Academic)

Sister journals https://royalsociety.org/Journals/

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA (published by NAS)

Science (published by AAAS)

Systematic Biology (published by Oxford Academic)

Taxon (published by Wiley)

In addition, the International Biogeography Society publishes a general biogeography journal with a very strong editorial team, although it is not listed by Clarivate:

Frontiers of Biogeography (N.B. *not* a “Frontiers.in” journal)

Biogeographia is another society journal on the same publication platform

Oxford University Press provides information on other journals it publishes, including whether they are society owned, e.g.

Plant sciences http://www.oupplantsci.com/category/journals/

Similar information on all Oxford journals can be searched at https://academic.oup.com/

Other university presses exist (Unversity of Chicago, University of California, Stanford, etc).