Oligoryzomys is an intriguing genus of sigmodontines that is distributed in almost all ecoregions of South America and continental Middle America. How did it get to be so diverse and distributed so broadly?

Above: A Patagonian specimen of Oligoryzomys longicaudatus, a species representative of one the fastest and geographically wide radiation of Neotropical mammals (photo credit: Dario Podesta).

Recent studies about the diversity of New World rodents, especially the mice and rats of the subfamily Sigmodontinae, show that their diversification started at the end of the Middle Miocene (ca. 12 Mya; Parada et al. 2021), reaching an impressive diversity of more than 400 living species in this period of time. Sigmodontine species richness is far from being completely characterized as shown by the frequent descriptions of new living species and even genera. Among sigmodontines, there is an intriguing genus that can be found in almost all ecoregions of South America and continental Middle America, the genus Oligoryzomys. This large distribution is only compared among mammals with that of the medium- and large-sized genera Conepatus (skunks), Didelphis (opossums), Procyon (raccoons) and Puma (cougar). Oligoryzomys encompasses 32 living species of long tailed mice; this species richness is among the largest among sigmodontine genera but is far below those of the genera Thomasomys, mainly distributed in the Tropical Andes and formed by 47 species, and Akodon, distributed in most of South America except Amazonia and most of Patagonia and formed by 31 species. Remarkably, Oligoryzomys is a much younger lineage (ca. 2.6 Mya old) than Thomasomys (ca. 4.22 Mya) and Akodon (ca. 3.8 Mya old). Another issue of interest is that several species of long tailed mice are the primary reservoir of distinct strains of hantaviruses that in humas cause Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome.

Cover image article: (Free to read online for two years.)

Hurtado, N. & D’Elía, G.(2022). Historical biogeography of a rapid and geographically wide diversification in Neotropical mammals. Journal of Biogeography, 49, 781–793.https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14352

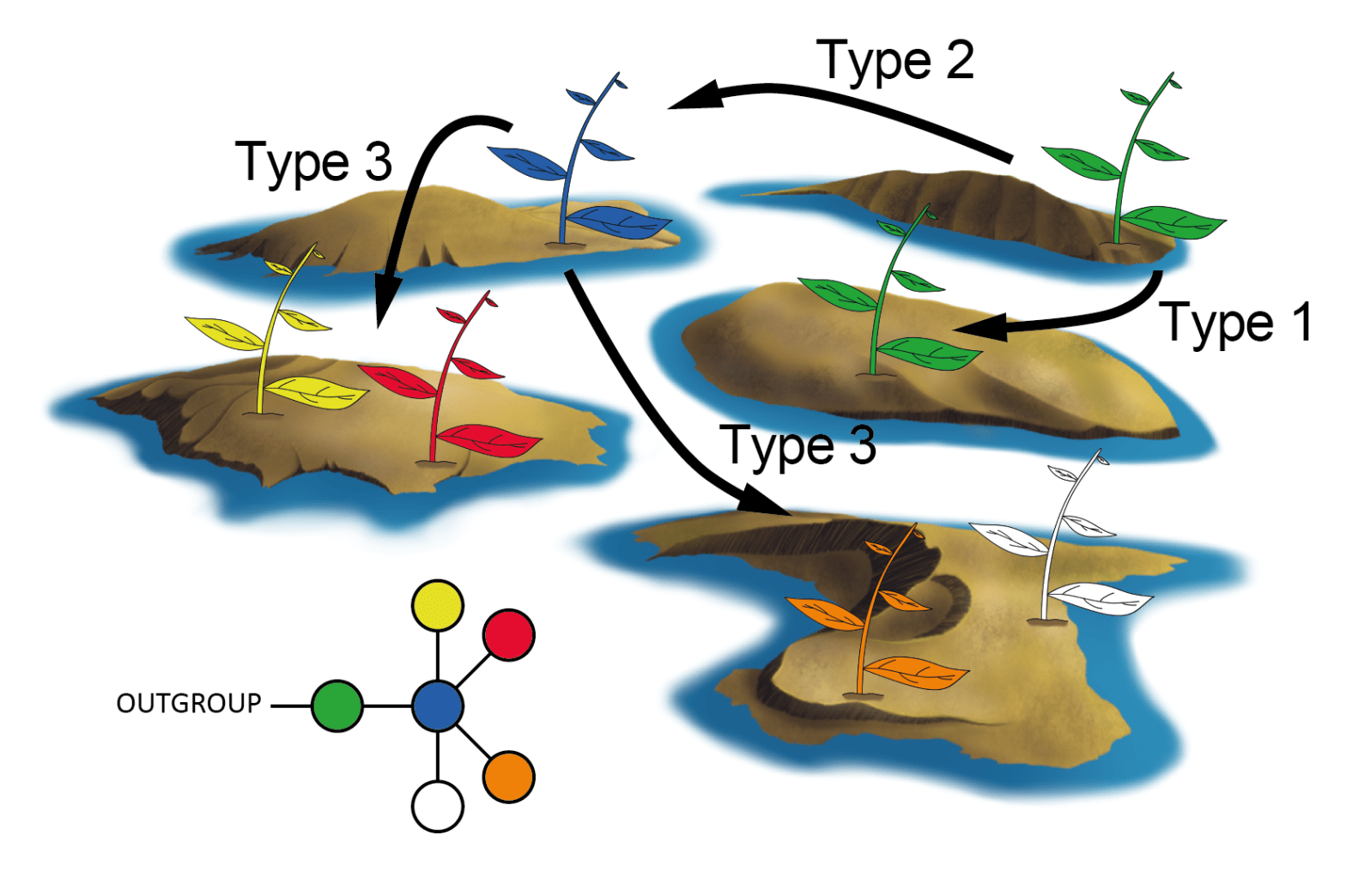

Amazed by the large diversity and geographic distribution of Oligoryzomys and their epidemiological relevance, which we collaborate to uncover and characterize the genus in previous studies, and here we designed a new study aimed to explain how this genus reached its enormous distribution and diversity in such a short period of time. After gathering samples from our own fieldwork, loans from museum collections and colleagues, we collected sequences of five genes. Then, we reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships among long-tailed mouse species using coalescence methods and dated their divergence times and found the biogeographic model that best describe the type and sequence of biogeographic events to explain the genus’ diversification.

Historical biogeography of the genus Oligoryzomys.

We corroborated that Oligoryzomys has a higher diversification rate than that of the Thomasomys and Akodon, the most species rich genera of the subfamily. We found that the most recent common ancestor of the genus, which lived ca. 2.6 Mya, was distributed in a large area in the lowlands of northern South America. Then, this ancestor, after a series of vicariant and dispersal events, colonized southern South America, the Andes and part of Middle America. This fast and geographically wide Pleistocene radiation is complex and involves events previously suggested for other groups of rodents (e.g., Andean diversification) and Neotropical fauna (e.g., connection between Amazonia and Atlantic forests), and others that are novel for rodents and for the most part for the South American mammals (e.g., the identification of the Chaco as a center of diversification).

However, much remains to be learned about the diversification of Oligoryzomys. One key fact that keeps us motivated and curious to understand why long-tailed mice constitute such a marvelous radiation is which trait or set of traits, either physiological, life history or morphological, has/have prompted this fast and geographically broad radiation? We hope that in the near future, with the analysis of additional data (hopefully at a genomic scale, conducted by us and several other colleagues, we will gain a deeper understanding of the radiation of Oligoryzomys. And then, we hope to explain how this radiation is related with the diversification and presence of strains of hantaviruses in several species of Oligoryzomys.

Written by:

Natali Hurtado (1) and Guillermo D’Elía (2)

(1) Research Associate, Centro de Investigación Biodiversidad Sostenible – BioS. Lima, Perú.

(2) Professor, Instituto de Ciencias Ambientales y Evolutivas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile; and Curator, Mammal Collection at the Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile

References:

Hurtado, N. & D’Elía, G.(2022). Historical biogeography of a rapid and geographically wide diversification in Neotropical mammals. Journal of Biogeography, 49, 781–793.https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14352

Parada, A., Hanson, J., & D’Elía, G. (2021). Ultraconserved elements im- prove the resolution of difficult nodes within the rapid radiation of Neotropical Sigmodontine rodents (Cricetidae: Sigmodontinae). Systematic Biology, 70(6), 1090–1100. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syab023

Additional information:

@NataliHurtadoMi; @GuillermoDElia, https://sistematica.cl