Victor Noguerales is a postdoc at the Instituto de Productos Naturales y Agrobiología in the Canary Islands – Spain. He is a phylogeographer interested in elucidating the mechanisms generating biological diversity, from populations to communities. Here, Victor shares his work on spatial hypotheses testing the processes promoting the genetic structure in a halophilic grasshopper.

Víctor Noguerales after completing a soil sampling campaign in Troodos mountain range, Cyprus (Photo credit: Emmanouil Meramveliotakis).

Personal links. Website | Research Gate | Twitter

Institute. Instituto de Productos Naturales y Agrobiología (IPNA-CSIC) – Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain.

Academic life stage. Postdoctoral researcher

Major research themes. I am interested in studying the mechanisms shaping spatial patterns of genetic variation at different biological levels of organization, from populations to communities. To deal with this question, I harness the power of genomic data, which I integrate into a multidisciplinary framework. In this sense, my research aims to decipher how geography, landscape structure and climate, along with their spatio-temporal dynamics, determine (i) gene flow patterns among populations (population genetics), (ii) diversification among lineages and species (phylogeography and phylogenetics) and (iii) composition and assembly of ecological communities (metabarcoding and community ecology). Broadly speaking, I am trying to provide some insights into our understanding of how biological diversity arises and responds to changing abiotic and biotic factors over space and time.

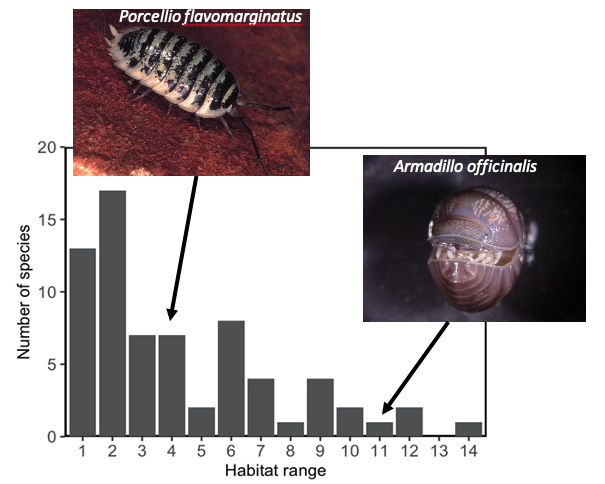

Current study system. I am fascinated by arthropods as they are highly diverse, exhibit a tremendous ecological and morphological diversity, and, in general, are poorly known fractions of biodiversity. During recent years, I have been studying grasshoppers with a special emphasis on taxa distributed in montane and halophilic (i.e., environments with high salt concentrations) habitats and whose evolutionary histories are often determined by intricate phenomena of geographic isolation and hybridization. Most recently, I am turning my attention to study soil arthropod communities (e.g., mites, springtails and beetles), which I use as study models to understand processes structuring spatial biodiversity patterns across forest habitats of Mediterranean islands.

Female and male of the saltmarsh band-winged grasshopper (Mioscirtus wagneri) on the typical salt crust covering the hypersaline lagoons during summer period (Photo credit: Pedro J. Cordero).

Recent paper in JBI. Noguerales, V., Cordero, P.J., Knowles, L.L. & Ortego, J. (2020) Genomic insights into the origin of trans-Mediterranean disjunct distributions. J. Biogeogr. 2021;48:440–452. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14011

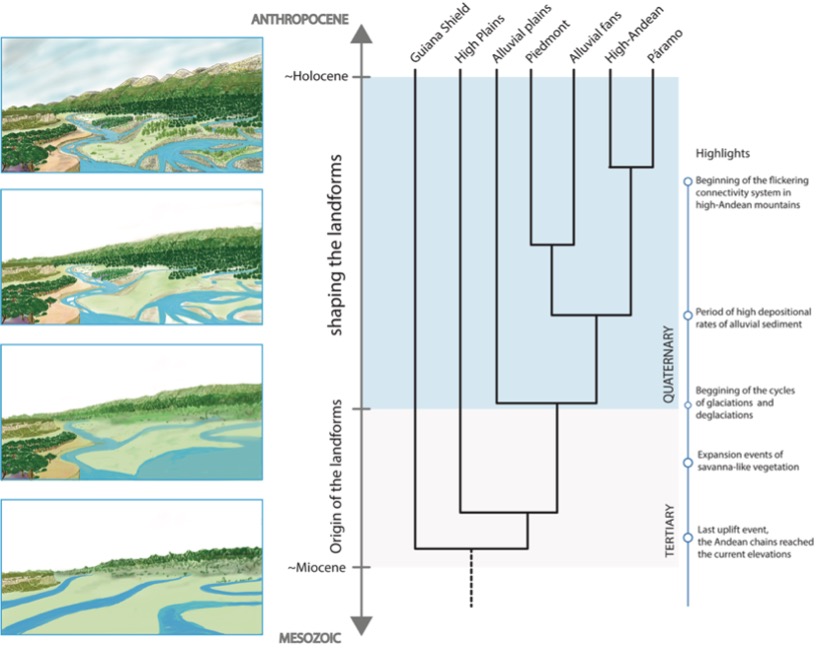

Motivation behind this paper. Previous research had investigated the factors underlying the phylogeographic structure of the saltmarsh band-winged grasshopper within the Iberian Peninsula. However, the questions concerning (i) the putative relict character of the western European populations and (ii) the tempo and mode of diversification throughout its entire Mediterranean distribution remained unexplored. Dispersal followed by vicariance promoted by the desiccation of the Mediterranean Sea during the Messinian Salinity Crisis (5.93-5.96 Ma) has been traditionally proposed as the driving factor behind the disjunct distribution that this and many other Mediterranean halophilic organisms currently exhibit. However, could more recent landscape change events have shaped similar distributional patterns? Whether to support or reject these hypotheses has long remained unclear given the paucity of empirical studies that have explicitly evaluated the relative importance of ancient versus contemporary landscape dynamics. That is, two motivations triggered the development of this study: we had a highly suitable study system for shedding light into this long-standing biogeographic paradigm, and we hoped to gain novel insights using a spatially-explicit perspective.

Halophilic vegetation in Peñahueca lagoon (Toledo, Spain) which constitutes the habitat of saltmarsh band-winged grasshopper (Mioscirtus wagneri; Photo credit: Pedro J. Cordero).

Key methodologies. This study combined methodological tools from landscape genetics (spatially explicit testing of biogeographical hypothesis) and phylogenomics (genealogical inference and divergence time estimation). Briefly, we constructed alternative scenarios of contemporary and historical population connectivity corresponding to the spatial configuration of emerged landmasses and climatically suitable areas during the present-day, Last Glacial Maximum (21 kya) and Messinian period (5.93-5.96 Ma). Then, we inferred gene flow for each hypothetical scenario by modeling individual movements over the landscape in a similar way to an electric circuit (i.e., circuit theory). Finally, the landscape scenario with the highest statistical support (i.e., the one best explaining the observed population genetic differentiation) was further assessed in the light of coalescent-based inferences of divergence times and phylogenomic relationships among populations. This multidisciplinary perspective combining genome-wide nuclear data and high-resolution spatial information arises as a powerful approach to provide key insights into our understanding of how local landscape dynamics ultimately shape biogeographic patterns.

Unexpected challenges. The saltmarsh band-winged grasshopper only inhabits scattered patches of a particular vegetation type associated with hypersaline lagoons that present a highly fragmented distribution at local and regional scales. Although it has specific ecological requirements, this grasshopper is not narrowly distributed but shows a transcontinental distribution range: from Iberia to northern Africa, the Middle East and beyond. This definitively sounds very appealing from a biogeographic point of view. Yet, sampling individuals and populations of this species across the Mediterranean is like looking for a needle in a haystack. So, probably the most challenging aspect of this study has been to collect enough samples from all the putative subspecies across its entire Mediterranean distribution range. Gathering all the samples took a long time (about seven years), but it was an amazing experience. Those steppe-like halophilic habitats are some of the most beautiful landscapes that I have ever contemplated!

(right) Male saltmarsh band-winged grasshopper (Mioscirtus wagneri); (left) Detail of the leaves of shrubby sea-blite (Suaeda vera), the host plant which the saltmarsh band-winged grasshopper (Mioscirtus wagneri) depends for feeding and shelter (Photos credit: Pedro J. Cordero).

Major results. Our analyses revealed that the genetic variation pattern of the species is the result of a post-Messinian colonization process followed by habitat fragmentation driven by Pleistocene climatic fluctuations. Of particular interest is the result demonstrating the permeability to gene flow of the Strait of Gibraltar, a phenomenon linked to the sea-level drops occurring during the Pleistocene cold stages. Such findings would highlight the capability of the species, despite its limited dispersal ability, to track and colonize suitable habitats during the last thousands of years. These results thus contradict prior hypotheses on the determining role of ancient range expansions during the Messinian Salinity Crisis (5.93-5.96 Ma) and long-term persistence in relict habitats in shaping the disjunct distribution of numerous steppe-like and halophilic Mediterranean organisms. Overall, this study stresses the power of bridging spatially explicit approaches and phylogenetics within the field of evolutionary biogeography to discern the relative role that different historical and contemporary landscape dynamics have played in promoting the observed biogeographic patterns.

A view of the Salicor lagoon (Ciudad Real, Spain) in early summer, showing the typical halophilic vegetation ring (Photo credit: Pedro J. Cordero).

Next steps for this research. The next steps revolve around our unexpected finding of the highly divergent lineages that present a parapatric distribution in Northern Africa. This finding opens the door to investigate the extent to which local adaptation followed by reinforcement and neutral processes linked to long-term isolation in cryptic refugia have synergistically determined that striking genetic differentiation pattern. The answer to this question would require a fine-scale sampling along the potential contact zones in Morocco and Tunisia, so we are planning further fieldwork in northern Africa, which I have wished for a long time!

If you could study any organism on Earth, what would it be? I feel lucky as I am studying the organisms that I most like on Earth. However, a different group of arthropods has lately attracted my attention: pseudoscorpions (Arachnida: Pseudoscorpiones). The first time I saw a pseudoscorpion in nature was just a couple of years ago while collecting soil mesofauna from leaf litter of golden oak forests (Quercus alnifolia) in Cyprus. And, honestly, I got impressed! They look so cool with their tiny pedipalps! Pseudoscorpions are an ancient lineage of arachnids whose origin dates back to the Devonian period. They are very small organisms (< 3-4 mm, at least the species I have spotted), so they easily go unnoticed. Despite their small body size and – apparently – reduced dispersal capability, they can actually move long-distances by attaching to other arthropods like flies and beetles, or even to some mammals, including bats. Amazing, isn’t it? I must admit that my knowledge about this group is still very limited, however, I wonder how much cryptic diversity they might hide and how their particular mode of dispersal affects their biogeographic patterns.