Jorge Cruz Nicolás is an evolutionary ecologist, currently working towards his PhD at the Instituto de Ecología, UNAM. He uses genetic tools to study population genetic processes in tree species. Jorge shares his recent work on identifying proxies for genetic diversity based on expectations of the niche centrality hypothesis.

Jorge Cruz sampling in a forest of Abies religiosa in Mexico state.

Personal links. Twitter

Institution. Instituto de Ecología, UNAM

Academic life stage. PhD

Major research themes. Ecology and evolution of plants, especially of trees, using genomic tools to explore questions about divergence and speciation.

Current study system. I currently study fir trees from the genus Abies. In their subtropical Meso-American range, Abies firs are found in small mountain refuges, for example, in the Mexican Highlands, above 2000 m asl. (N.B. This restricted distribution contrasts with that seen in North American populations, with lower elevations, 700 to 3,600 m asl). Volcanic activity in the recent geological history of the Mexican highlands generated sky-islands and promoted colonization–extinction dynamics. Patterns of population structure, connectivity, and genetic diversity among Abies firs in the Mexican Highlands is complicated, but provides an interesting chance to study how ecological and evolutionary processes shape patterns of diversity.

A panoramic view of Abies religiosa in Mexico state.

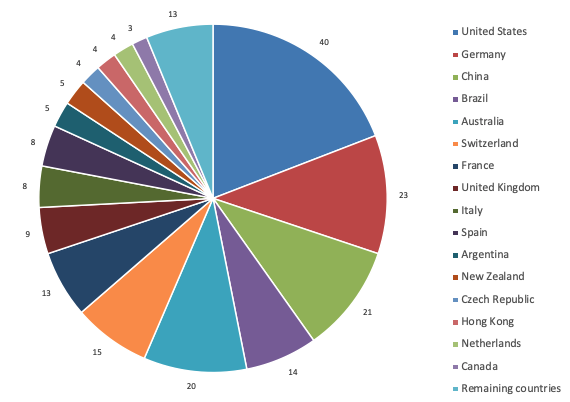

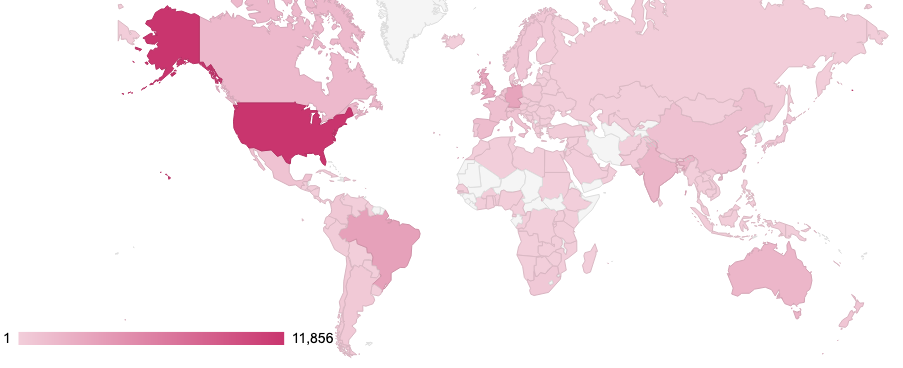

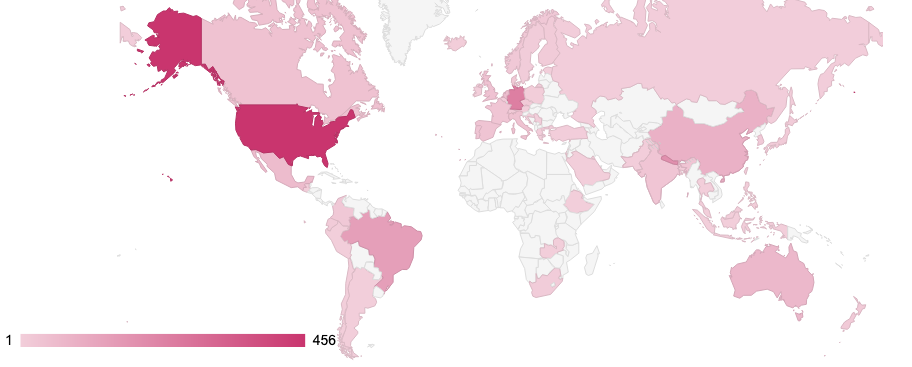

Recent paper in JBI. Cruz-Nicolás J, Giles-Pérez GI, Lira-Noriega A, et al. Using niche centrality within the scope of the nearly neutral theory of evolution to predict genetic diversity in a tropical conifer species-pair. J. Biogeogr. 2020; 47:2755–2772. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13979

Motivation behind this recent paper. Because Abies firs are under threat from climate change, it is important to understand the population genetic properties of this species to assess their response to increasingly warmer conditions. Greater genetic diversity is expected to aid in adaptation to climate change, but it can be very hard to measure genetic diversity across a species’ entire range.

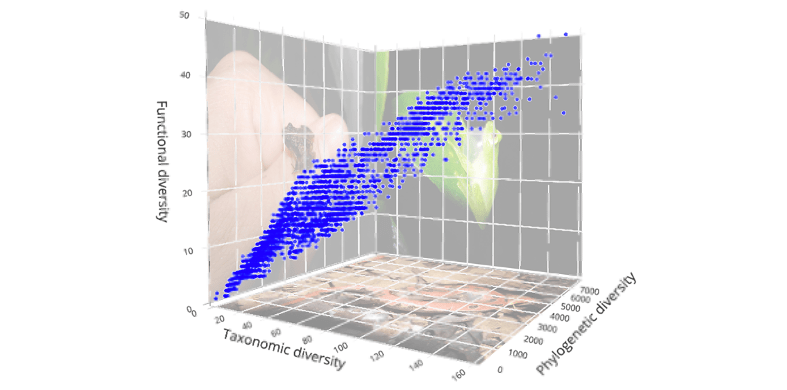

We therefore wanted to identify proxies for genetic diversity, using the principles of the niche centrality hypothesis as a guide. The niche centrality hypothesis predicts that population abundances are larger nearest a species’ niche centroid, assuming “optimal environmental conditions”. Because larger populations are expected to harbour greater diversity, it is possible that populations closer to a species’ niche centroid might also have greater genetic diversity. However, this assumption has not been tested well, so we explored whether niche centrality, together with other factors (estimated area, geographic history) could explain patterns of genetic diversity in Abies firs from Mexico.

Key methodologies. We measured genetic diversity with two kinds of markers: nuclear microsatellites and nuclear gene coding sequences in two species of genus Abies in Mexico. We obtained measures of genetic diversity as number of alleles, expected heterozygosity, nucleotide diversity, and a measure of partial deleterious variants (πN/πS). This last measure, πN/πS, is interesting because it describes the ratio of genetic changes that lead to coding (amino acid) differences (πN) to those that do not change coding (πS). We would expect that deleterious mutations are higher in populations with smaller effective population sizes based on the nearly neutral theory of evolution, with the expectation that marginal populations might accumulate more partial deleterious variants (and have higher πN/πS) than stands near the centroid. In other words, purifying selection is weaker in small effective population sizes. Also, we tested the relationship of estimated area and longitude and with measures of genetic diversity to infer possible historical effects in accumulation of genetic diversity.

Major results. We found that associations between genetic diversity measures with niche centrality or other factors were mixed. Most of the measures did not exhibit a clear association with niche centrality. For example, πS and number of alleles were more strongly predicted by longitude, reflecting historical expansion. Heterozygosity was affected by the process of genetic drift, especially in populations which have suffered severe bottlenecks and have remained isolated for long periods of time. However, we did find that the πN/πS ratio was positively correlated with niche centrality. Populations closer to niche optimum therefore have a lower accumulation of deleterious mutations, in other words, this measure was more related to the ecological conditions rather than phylogeographic factors. Higher values of πN/πS indicate that purifying selection in marginal populations has been relaxed, as consequence of reduction in effective population sizes, and might be an indicator of reduced adaptive potential in such population. These results suggest that a good knowledge of both phylogeographic and ecological factors is necessary to understand the accumulation of genetic diversity.

Unexpected outcomes. We had not initially planned to consider the πN/πS ratio and we were just going to focus on genetic variation measures (number of alleles, heterozygosity, nucleotide diversity). But when my supervisor, Ph D. Juan Pablo Jaramillo Correa, came back from sabbatical, he suggested that we consider a measure that reflects changes in the allelic frequency spectrum, which led to us using the πN/πS ratio for the accumulation of deleterious mutations. This turned out to be a great decision because we found that πN/πS is significantly correlated with niche centrality expectations and can provide a good proxy for genetic diversity.

(left) Larger trees of Abies religiosa in Puebla state, México. (right) Ovulated cone of Abies religiosa.

Next steps. The next step would be verifying the results of niche centrality with more populations, using genomic and demographic data in different organisms, to verify whether this trend with niche centrality is maintained. If true, niche centrality could be a good proxy of effective sizes in many species without data of genetic diversity. There are certainly important consequences for conservation and for species management if easy to obtain proxies for genetic diversity can be reliably obtained.

If you could study any organism on Earth, what would it be? I would like to study the mistletoes: these plants have coevolved with many species of trees across very contrasting environments. These interactions could tell us about the historical dispersions, adaptations, and even health of forests, which are very important in the context of global warming. I would love to establish common garden experiments to compare ecological niche modelling with experimental data.

Anything else to add? Currently, I study aspects of speciation in genus Abies in Mexico with their evolutionary implications. I study the phylogenetic relationships of Mexican firs with data derived from genotyping-by-sequencing. The questions are (i) do phylogenetic clades (if present) fit better the taxonomic description of firs or the geographic regions of Mesoamerica; (ii) can we detect more than one fir expansion wave into Mesoamerica; (iii) is there any evidence for a species radiation; and, if so (iv), can adaptive or non-adaptive forces be inferred within the patterns of diversity at candidate genes?

.

. .

. .

.

.

.