Mouse-goats, ‘demons of the forest’, and other insular bovids have short and robust limbs. Why? The ‘low gear’ hypothesis had never been tested until we decided to fill this gap with a quantitative investigation of the causal forces influencing the acquisition of this peculiar type of locomotion.

Above: Skulls of a tamaraw (Bubalus mindorensis), a dwarf buffalo endemic to Mindoro island, highlighting different stages of ontogenetic development (Mammal Collection; Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago).

The Dutch palaeontologist P. Y. Sondaar already noticed in the 1970s that many insular ruminants, and to a lesser degree insular elephants and hippopotamuses, exhibited short and robust limbs. He explained this as an adaptation for a peculiar type of gait, that he described and named ‘low gear’ locomotion. Sondaar and other researchers after him mentioned several examples, including the iconic Balearian mouse-goat (Myotragus balearicus). They believed that this stout structure of the limbs would be advantageous, in the absence of predators, for low-speed walking in mountainous environments.

Bovids are intriguing elements of insular faunas and encompass phyletic dwarfs that occurred or are still living on islands located in different regions, from Southeast Asia to the Mediterranean. I have previously investigated their body size evolution on islands, (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jbi.13197) and we decided to concentrate on the bovid family again in this study. Some of the best-known cases of ‘low gear’ locomotion include the already mentioned Myotragus as well as the tamaraw, a living dwarf buffalo endemic to Mindoro in the Philippines. We focused on the two main morphological traits associated with this peculiar type of gait, that is short and robust metapodials, and we calculated response variables in 21 extinct and living insular bovids. We assembled data on their life history and ecology and on the physiography of 11 islands. We estimated 10 predictors, including 4 topographic indices, and assessed their contextual importance by combining statistical and machine learning methods.

FROM THE COVER: Rozzi, R, Varela, S, Bover, P, Martin, JM. Causal explanations for the evolution of ‘low gear’ locomotion in insular ruminants. J Biogeogr. 2020; 47: 2274– 2285. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13942

We demonstrated that the evolution of ‘low gear’ locomotion in insular ruminants does not result simply from phyletic dwarfing and from the absence or scantiness of predators in the focal communities. Instead, we showed that release from competitors on species-poor islands plays an essential role in prompting adaptations for this peculiar type of gait. While island topography is not as relevant as interspecific dynamics in influencing the evolution of the focal morphological traits, the amount of mountainous terrain occurring on each island seems to significantly affect the evolution of robust metapodials in insular bovids. All in all, our study supports the idea that the evolution of ‘low gear’ locomotion would be the product of a complex interplay of biotic and abiotic factors, and calls for caution in drawing conclusions on this phenomenon on the basis of single, albeit significant cases.

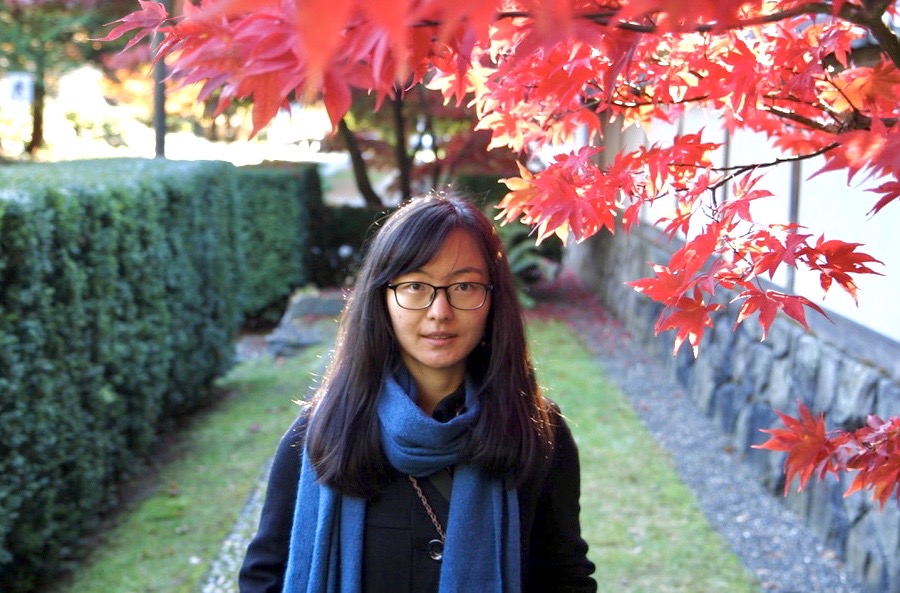

(Left) Roberto measuring a skull of the iconic mouse-goat, Myotragus balearicus, at IMEDEA – Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies, Mallorca. M. balearicus was an endemic caprine that lived on Mallorca and Menorca during the Late Pleistocene and Holocene, before becoming extinct following the arrival of humans around 4300 years ago. (Right) Roberto embraced by the horns of a river buffalo, Bubalus bubalis, in the mammal collections at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington DC.

An unexpected outcome of this study was to find out that, even though the most extreme cases of ‘low gear’ locomotion occurred on islands with no mammalian predators, our models did not show a significant relationship with this predictor. To sum up, the a priori hypothesis that this low-speed gait would simply result from predator release on islands needed to be reconsidered. Discussing the role of ecological and topographic traits in influencing the evolution of ‘low gear’ locomotion was challenging, because of their complex interaction and the variation in morphological responses to those factors within insular bovids. In fact, we observed a variety of trait combinations, with species exhibiting different degrees of robustness and shortening of metapodials, and different responses to many of the focal predictors by species belonging to one or the other subfamily of bovids in the study. Thus, much effort is still needed to verify how robust island syndromes are and to understand their causation. In this vein, I am planning to continue to explore other peculiar traits exhibited by these fascinating animals. In particular, I am looking forward to implementing advanced methodologies in palaeoneurology to investigate patterns of brain size variation and changes in the degree of cortical folding in insular Artiodactyla.

More broadly, my research focuses on the evolution and extinction of mammals on islands. There is some urgency to this. In response to the special characteristics of island environments, these animals often undergo fascinating evolutionary changes, including changes in body size and in the morphology of their skull, brain, teeth and limbs. My collaborators and I are currently focusing on how the evolutionary changes undergone by insular mammals predispose them to heightened extinction risk. I am investigating the relationship between their peculiarity and their fragility, as many of these evolutionary marvels are often threatened or already extinct. In collaboration with other palaeontologists, mammalogists and biogeographers, we are integrating data on fossil and living insular mammals to document their extinctions across large scales of time and to inform conservation strategies.

Mounted skeleton of the extinct (Middle Pleistocene) Sicilian dwarf elephant

Palaeoloxodon falconeri at Museo Geologico ‘G. G. Gemmellaro’, Palermo, Sicily.

The application of theories and analytical tools of palaeontology to provide valuable information for conservation planning is one of the key drivers of my research. Many threatened island mammals receive scarce conservation action because they are deemed ‘uncharismatic’ and fail to attract funding. Palaeontological studies have the potential to produce detailed information on the evolutionary history and uniqueness of these species and, thus, draw attention to their conservation value. I did my PhD on insular bovids and I was saddened to read that, in a recent study on the full collection of mammals from the Prague Zoo, the lowland anoa (Bubalus depressicornis) was ranked as one of the least attractive species. Sometimes referred to locally as Sulawesi’s ‘demon of the forest’, anoas never cease to inspire my research and, as a member of the IUCN SSC Asian Wild Cattle Specialist Group (https://www.asianwildcattle.org/), I feel it is important to keep highlighting how beautiful and unique these dwarf buffaloes really are.

The evolutionary anomalies of island life are among the most spectacular phenomena in nature, yet islands contain a disproportionately higher amount of threatened and extinct biota compared to continents. I have always found the ecologically naive and fragile nature of these taxa extremely intriguing. Dwarf elephants and hippos, giant rats and shrew-like insectivores larger than a cat, short-legged bovids with stereoscopic vision, deer with bizarre antlers, etc. Both the fossil record and islands today are home to mesmerizing mammal species.

Written by:

Roberto Rozzi

Postdoc, German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig

For more information: https://twitter.com/Rozzi_Roberto | https://scholar.google.it/citations?user=ZTz5g0QAAAAJ&hl=en

.,

(Left) View of Monte Tuttavista, one of the major Sardinian localities yielding Quaternary fossil vertebrates ranging in age from the Early to Late Pleistocene. Bovids of the so-called ‘Nesogoral group’ were also recovered from this site and included in our study. (Centre) Roberto Rozzi at Gásadalur, Vágar, Faroe Islands.

(Right) Crystal clear waters of Caló den Rafelino, Mallorca, where remains of the earliest representative of the Myotragus lineage were found (Myotragus palomboi; Early Pliocene).