André Luís Luza is a postdoc at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Brazil. He is an ecologist with special focus on community ecology, macroecology, and macroevolution. Here, André shares his recent work on functional diversity patterns of reef fish, corals and algae.

André Luís Luza is currently a post-doctoral researcher at the Universidade Federal de Santa Maria – Rio Grande do Sul/Brazil.

Personal links. Twitter | Personal Website

Institute. Department of Ecology and Evolution, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Brazil

Academic life stage. Postdoc

Major research themes. I study community ecology, macroecology, and macroevolution, with a strong focus on integrating theoretical frameworks and methodological approaches from these fields. My primary interest lies in investigating how past and present dynamics shape current biodiversity patterns.

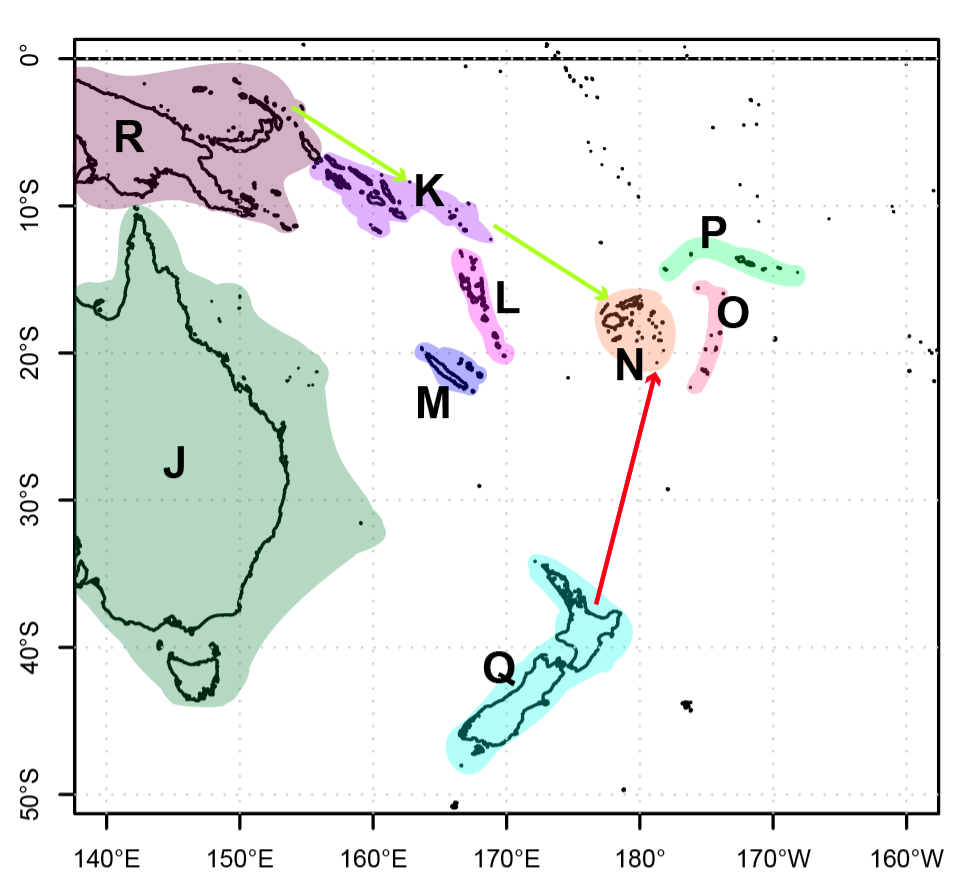

Current study system. Shallow-water reefs occur along the coastal tropical and subtropical areas of the global ocean and support a multitude of unique interactions among organisms and between organisms and their environment. Brazilian shallow-water reefs form an interesting and often intriguing study system, especially due to their unique evolutionary history. Isolated from the Indo-Pacific and Caribbean reef biodiversity hotspots for over 3 million years, these reefs have evolved distinct patterns of endemism, species richness, and trait diversity. The influence of freshwater and sediment discharge from the continent’s large rivers adds further complexity. Despite their remarkable characteristics, the geographical patterns of reef diversity in the Brazilian Biogeographical Province and the underlying driving factors are yet to be fully understood.

Recent JBI paper. Luza, A. L., Aued, A. W., Barneche, D. R., Dias, M. S., Ferreira, C. E. L., Floeter, S. R., Francini-Filho, R. B., Longo, G. O., Quimbayo, J. P., & Bender, M. G. (2023). Functional diversity patterns of reef fish, corals and algae in the Brazilian biogeographical province. Journal of Biogeography, 50, 1163– 1176. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14599

Motivation behind this paper. Our recent paper was motivated by two main factors. Firstly, while interactions between organisms and environmental gradients can generate spatially congruent patterns of diversity across reef ecosystems, this aspect had not been evaluated for fish, corals, and algae in the Brazilian reefs. Secondly, we aimed to address a gap in the understanding of functional diversity patterns by assessing spatial congruence among distantly related groups. Traits such as size, morphology, feeding behavior, and mobility play a vital role in how organisms associate and respond to the environment. Thus, our study aimed to fill this knowledge gap in this extensive biogeographical province using a trait-based approach.

Reef fish, including endemic parrotfishes (Labridae family), sharing the seascape and interacting with algae and endemic corals in the Abrolhos Bank, northeast Brazil. Reefs in Brazil develop under turbid and nutrient-rich waters, producing unique assemblages of species. Photo credit: João Paulo Krajewski

Key methodologies. Our recent paper was developed as part of an ecological synthesis working group called ‘ReefSYN’ (SinBiose, CNPq). The ReefSYN collaborators collected and compiled occurrence data and functional traits of fish and benthic reef organisms along the Brazilian coast and oceanic islands. This unprecedented effort in building comprehensive databases and conducting cross-taxon analyses enabled us to assess diversity patterns in Brazilian reefs using spatially replicated local data.

To assess spatial congruence, we employed Bayesian multivariate linear models, which are particularly suitable and innovative. These models allowed us to simultaneously evaluate: i) the spatial correlation between the functional diversity of reef fish, corals, and algae; ii) the influence of various factors (such as sea surface temperature and species richness) on the functional diversity of each group; and iii) the residual spatial correlation after accounting for these factors.

This approach enabled us to determine whether the existing congruence was driven by the modeled factors or by unaccounted variables. By leveraging these methodologies, our study provided new insights into the patterns of spatial congruence and the underlying drivers of functional diversity in Brazilian reefs.

Feeding aggregation of coney (Cephalopholis fulva, Epinephelidae family) in tropical rocky reefs of Fernando de Noronha Archipelago, northeast Brazil. Photo credit: João Paulo Krajewski.

Unexpected challenges. During our research journey, we encountered unexpected outcomes and challenges that enhanced the depth of our scientific inquiry. Matching occurrence and trait data for different organisms and conducting analyses across distantly related groups proved to be challenging. The sampling of reef fish and benthic organisms was carried out by separate teams, using different methods, which resulted in data being organized in various formats. Standardizing these datasets for interoperability required a collaborative effort and an exploration of the field of data science. Analyzing the functional diversity of distantly related groups presented another challenge, as organisms separated by significant phylogenetic distances share few common traits. Furthermore, the resolution of traits was higher for fish compared to corals and algae. To overcome these challenges, we delved into trait-based approaches, leveraging available traits to facilitate meaningful comparisons of functional diversity patterns across groups. These unexpected outcomes and challenges enriched our research journey, compelling us to employ innovative solutions and embrace interdisciplinary approaches to unravel the complexities of the Brazilian reef ecosystems.

Major results. The major finding of our recent paper reveals the spatial correlations in functional diversity among reef fish, corals, and algae in the Brazilian Province. Interestingly, we discovered weak to intermediate correlations in the patterns of functional diversity across these groups. Additionally, these patterns deviated from the classic latitudinal diversity gradient observed in other regions. Sea surface temperature (SST), species richness, and regional factors were identified as key determinants that influence the spatial correlations in functional diversity. Our study contributes to the field by shedding light on the factors that underlie the spatial congruence between groups of organisms. We demonstrate that both present factors (SST and species richness) and past factors (region) play crucial roles in shaping the observed spatial patterns. Importantly, we highlight the vulnerability of reef functional structure to cumulative anthropogenic impacts, such as climate change, pollution, and overfishing. These impacts have the potential to disrupt species composition, alter environmental gradients, and affect functional redundancy, posing a threat to the overall resilience of reef ecosystems.

The fire coral Millepora alcicornis and the Queen angelfish (Holacanthus ciliaris) in Abrolhos reefs (Brazil). Photo credit: João Paulo Krajewski.

Next steps for this research. The discovery of an overall low to intermediate correlation in functional diversity among reef fish, corals, and algae opens up intriguing avenues for future research. We aim to delve deeper into understanding the factors that have shaped this congruence and explore the functioning of these ecosystems, despite the weak relationships between organisms. Our next steps involve investigating the presence of ecological engineers or keystone species that drive crucial ecological fluxes and nutrient cycling, as well as their spatial distribution within the reefs. Additionally, we aim to assess the vulnerability of these key species to the impacts of climate change. Can Brazilian reefs simultaneously provide multiple ecosystem functions and services, despite low ecological congruence? These questions remain open and will guide our future investigations.

If you could study any organism on Earth, what would it be? If I were given the opportunity to study any organism on Earth, I would choose to concentrate on extinct organisms, specifically fossils of vertebrates. Fossils offer invaluable insights into the ecological and evolutionary processes that have shaped the patterns of biodiversity we currently observe. For instance, through the examination of fish fossils in conjunction with phylogenetic analyses, we can enhance our understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the weak association between reef fish and benthic organisms in the Brazilian province. This multidimensional approach would enable us to uncover the ecological and evolutionary dynamics that have influenced present-day reef ecosystems.

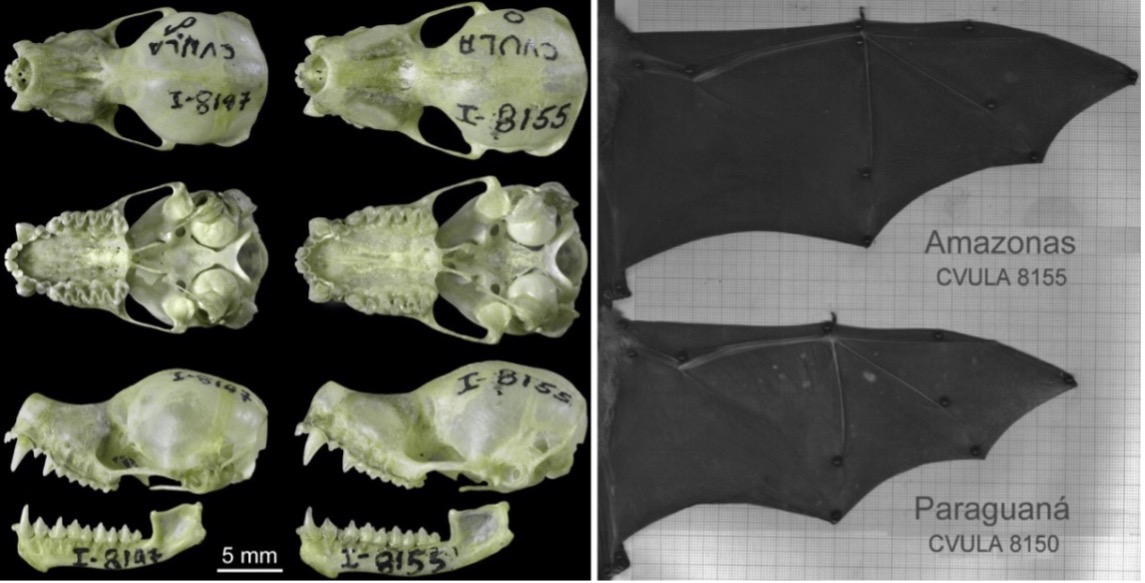

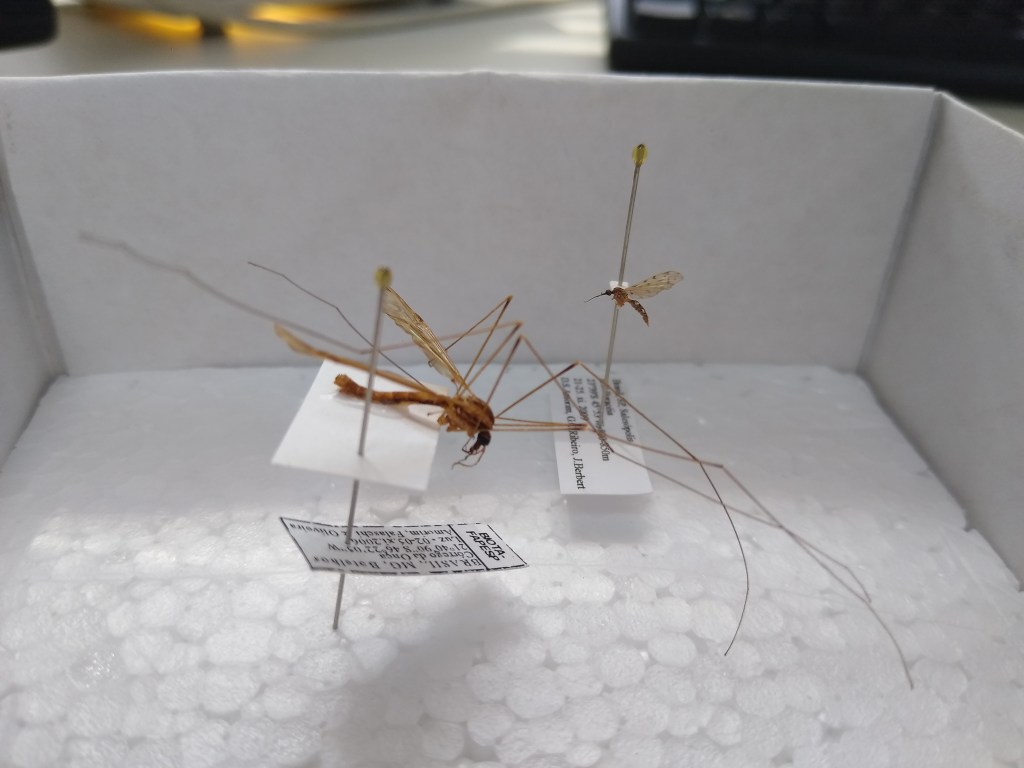

Anything else to add? In my journey as a biologist, I initially focused on studying non-volant small mammals in grassland and forest ecosystems, starting from my undergraduate years in Biology back in 2010. While collaborating on various research projects involving birds, amphibians, and mosquitoes, I had never worked with marine organisms before joining ReefSYN as a postdoctoral researcher in 2020. This presented an exciting challenge for me as I delved into the fascinating field of reef ecology. It wasn’t until March 2023, three years after becoming part of the ReefSYN working group, that I had my first diving experience. Currently, my research is centered around a project that combines macreecology, macroevolution, and paleontology. The project aims to unravel the mechanisms driving the emergence of the first mammals and understand the consequences of the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event. By bridging these disciplines, we hope to shed light on key evolutionary processes and their impact on the diversification of life.