The geographic ranges of mammals in Africa are limited in size by the variation in habitats across space (habitat heterogeneity), but surprisingly not by the variation in elevations (topographic heterogeneity). Mammalian ranges will be sensitive to future habitat destruction and alteration, as climate change and human impacts continue to intensify.

Above: The cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) is one of many African mammals whose range size may be constrained by the variation in habitats across landscapes, i.e., habitat heterogeneity (picture taken by Michael S. Lauer).

In the summer of 2019, I attended the Ecological Society of America’s annual conference in Louisville, Kentucky. I remember walking around a massive room with hundreds of posters, and as I made my rounds, I couldn’t help but notice that many of the posters had the word “heterogeneity” in their title. Fast forward a few months to the fall of 2019, when my co-author and aca-brother (Dr. Benjamin Shipley) introduced me to some of the aspects of mammalian biogeography that were still unknown. Fast forward again to the spring of 2020, when I took a course titled “Biodiversity on a Changing Planet” taught by my co-author and graduate advisor Dr. Jenny McGuire. Why am I listing three seemingly unrelated experiences? As it turns out, all three together served as the foundation of our recent paper. Had I not gone to the conference, I would not have internalized how important landscape heterogeneity (i.e., the variation in environmental conditions across space) is to ecology and biogeography. Had I not conversed with Ben, I would not have been initially enticed to study mammalian geographic ranges and the associated knowledge gaps. And had I not taken the course, I would have not been assigned the project that morphed into the initial draft of this paper. All of this is to say that sometimes the most exciting ideas come from a “heterogeneity” of experiences and perspectives.

Cover article: (Free to read online for two years.)

Lauer, D. A., Shipley, B. R., & McGuire, J. L. (2023). Habitat and not topographic heterogeneity constrains the range sizes of African mammals. Journal of Biogeography, 50, 846 – 857. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14576

Ultimately, it was the combined perspectives of myself, Ben, and Jenny that led us to ask the following question: are mammalian geographic range sizes in Africa more constrained by the variation in habitats (habitat heterogeneity) or the variation in physical elevations (topographic heterogeneity) across space? We knew from prior research that species ranges are constrained in heterogeneous landscapes because to co-exist, each species adapts to the specific environmental conditions of specific areas. But we wanted to take this idea a step further. We were motivated to compare the effects of habitat and topographic heterogeneity specifically because they represent two fundamentally different things about landscapes. Habitat heterogeneity is fluid, as habitats come and go rapidly depending on how climates change and how humans behave. Consider, for example, a landscape that is heterogeneous because it possesses small patches of intertwined forest and grassland habitats. Such a landscape could become rapidly homogeneous if its trees are cut down and it transforms into an extensive grassland. Contrast that to topographic heterogeneity, which is much more set in stone. A landscape that is heterogeneous because it is hilly is likely to remain hilly for a long time. Hills and mountains don’t disappear overnight.

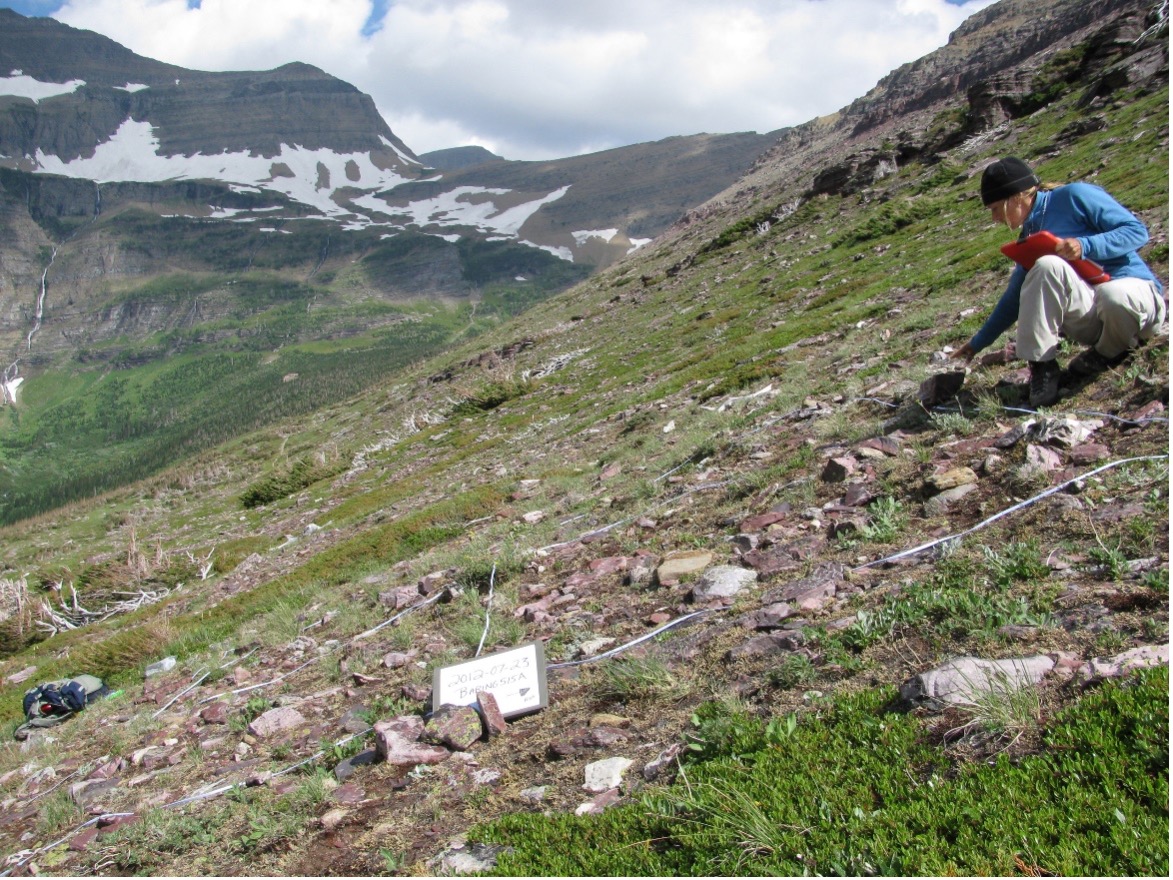

The landscape on the left has low habitat but high topographic heterogeneity, as it exhibits only forest habitat but is hilly. The landscape on the left is the opposite, as it exhibits forest, grassland, and aquatic habitats but is flat (pictures taken by Daniel A. Lauer).

At first, we were thinking that both habitat and topographic heterogeneity would at least have some constraining effect on species range sizes. But in a fashion that often makes science so exciting, we were surprised to arrive at an unexpected result. While we found evidence that habitat heterogeneity had a strong limiting effect on range size, our analyses suggested that topographic heterogeneity had no effect at all! This contrast became particularly interesting and important to us as we thought about its implications. Essentially the contrast suggests that when landscape heterogeneity limits mammalian ranges, it does so via its fluid, subject-to-change habitats, and not via its rigid physical structure. Consequently, the persistence and geographic occurrences of mammals may be highly susceptible to habitat change, destruction, and alteration by climate change and human land use. We channeled these ideas to think about how our results could be meaningful for both ecological theory and environmental conservation. Regarding the former – we were able to add a new layer of nuance to the theory of how landscape heterogeneity constrains ranges. And regarding the latter – we would suggest that conservation efforts should focus on the small-ranged mammals that occur in regions of high habitat heterogeneity, particularly considering that a small range can often mean a higher extinction risk.

Along our collaborative journey I learned many things, and together we opened some avenues for future researchers to explore. I internalized the power that many experiences, as well as ideas from other scientists, can have in forming a meaningful scientific question. I learned how cool it can be to answer such a question by collecting data from many sources and combining that data into a single analytical pipeline. And I learned that the most exciting science can emerge from the results that were wildly unexpected. Our work calls for an enhanced understanding of the specific species that live in regions of high habitat heterogeneity in Africa. What are these species? What are their functional traits and evolutionary histories? How do they compare to species that occur in more homogeneous environments? What would be the most effective conservation strategies to prevent their extinction? Time will tell, but for now we can say that the sky (or the heterogeneity of the landscape?) is the limit.

Written by:

Daniel A. Lauer (Ph.D. Candidate)1,2, Benjamin R. Shipley (Ph.D.)2, Jenny L. McGuire (Assistant Professor)1-3

1Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Quantitative Biosciences, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA

2School of Biological Sciences, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA3School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA

Additional information:

LinkedIn (Daniel Lauer): https://www.linkedin.com/in/daniel-lauer/

ResearchGate (Daniel Lauer): https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Daniel-Lauer-2

Twitter (Daniel Lauer): @DannyLauer

ResearchGate (Benjamin Shipley): https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Benjamin-Shipley

Instagram (Jenny McGuire): mapsnbones

Twitter (Jenny McGuire): @JennyMcGPhD

Webpage (Jenny McGuire): https://www.mcguire.gatech.edu